BY MICHELLE KUO

Editor’s note: This essay has been translated into traditional Chinese by Wenpei Lin. The translation was published in issue 118 of Forum in Women’s and Gender Studies (婦研縱橫), and the electronic file can be downloaded here.

【編按】本文由林紋沛譯為繁體中文。譯文〈「我們從自己的失去出發,伸出雙手擁抱我們傷害的人」:女性受刑人與凱西・布丹(Kathy Boudin)的人生故事〉刊登於《婦研縱橫》118期,電子檔可在此下載。

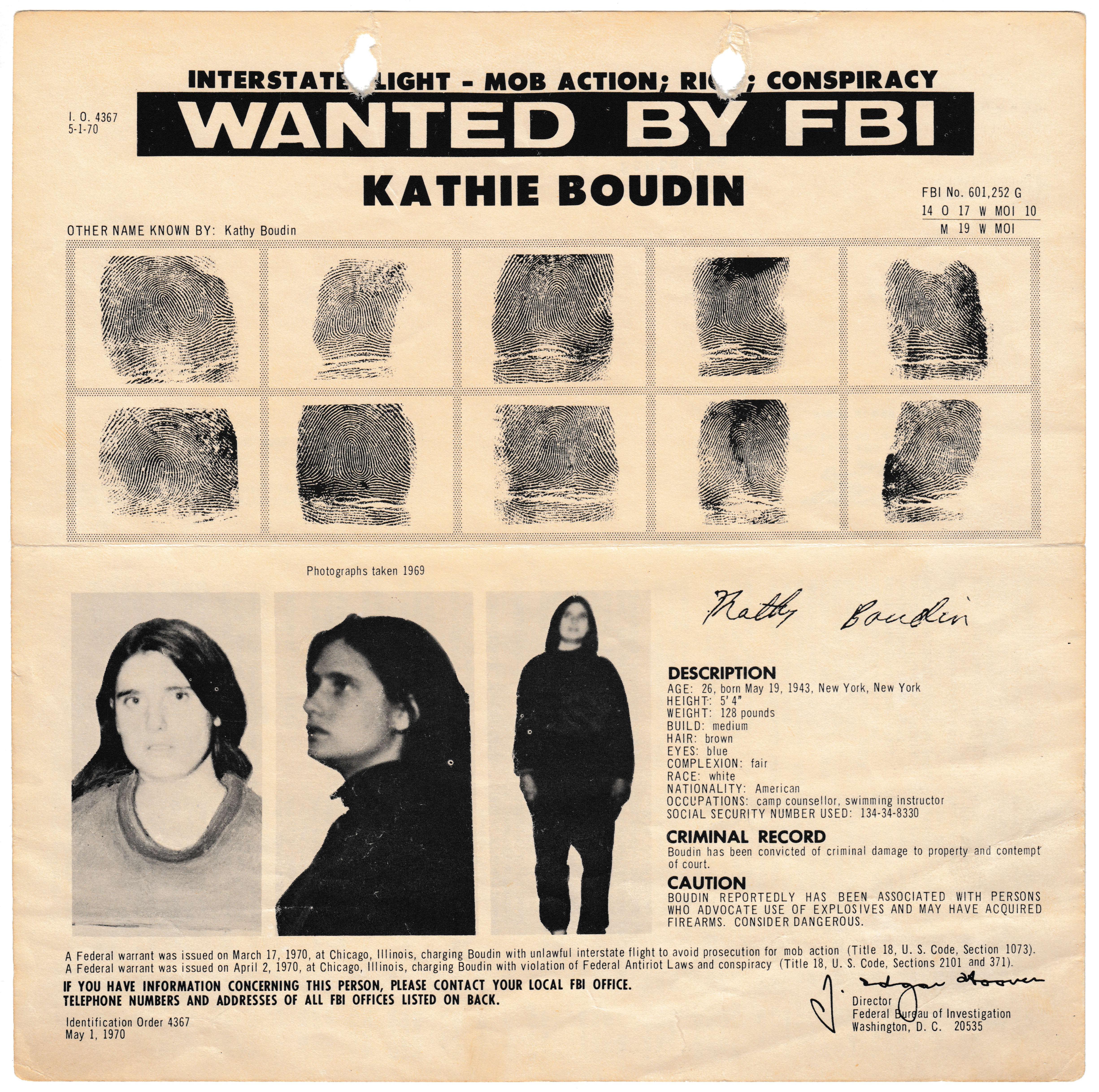

For those in her generation, the story of how Kathy Boudin landed in prison is well-known, riveting, and prone to sensationalism. In October 1981 the Black Liberation Army, a revolutionary party, robbed an armored van just outside New York City. Gunmen shot two police officers and a guard and stole 1.6 million dollars.

Boudin was unarmed, one of four getaway drivers. The father of her 14-month-old baby, whom she left with the babysitter earlier that day, was another. The couple were members of a communist faction of the Weather Underground, a radical organization that was formed to oppose the Vietnam War and American imperialism. They had been asked to participate in part because they were white; the police would be less likely to stop white drivers. Boudin was convicted of murder and given a life sentence in prison.

(Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Boudin’s illustrious pedigree contributed to the allure of the crime. Her father, Leonard, was a famous civil rights lawyer of his time, representing, among others, people accused of being Communist, as well as celebrities such as Paul Robeson, Daniel Ellsberg, and Dr. Spock. Boudin’s great uncle was a prominent socialist organizer and law professor at Yale. Their household had an intellectually “intimidating” atmosphere, as one person told the journalist Elizabeth Kolbert (Kolbert, 2001, p. 2). Boudin and her older brother were encouraged to speak, to make something of themselves. That brother would go on to graduate from Harvard College and then Harvard Law School; he became a federal judge. As Kolbert puts it, the Boudins “could be described as a classically ambitious, talented, and liberal New York Jewish family, were it not that they were almost too ambitious, talented, and liberal” (Kolbert, 2001, p. 3).

In the media, Boudin’s story prompted ridicule, contempt, hatred, amusement, and fascination: privileged girl becomes domestic terrorist. She, along with others such as Bernadine Dohrn, were the “granola terrorists, well-loved children of the middle-class who imagined themselves warriors for the dispossessed” (Posnock, 2018, p. 5).

But her own journey was complex, idiosyncratic, and reflective of the turbulent times in which she lived. Growing up, she dreamt of becoming a doctor, only to be dissuaded by the science classes at Bryn Mawr, where she attended. After graduating, she went to work in a working-class, Black neighborhood in Cleveland as a community organizer for the Economic Research and Action Project (ERAP), and lobbied on behalf of poor communities for services such as garbage collection. ERAP, in turn, was a part of the Students for Democratic Society (SDS), a radical student movement formed in Michigan to oppose the Vietnam War. Meanwhile, she was applying to law schools and was accepted. But she kept deferring. “I felt increasingly ambivalent about whether I could see myself moving toward a professional life,” she would tell Kolbert in 2001. “It seemed like it would perpetuate, in my own life, more privilege” (Kolbert, 2001, p. 3).

Boudin moved back to New York and into a communal house in Greenwich Village, living among members of the Weather Underground. But when a bomb accidentally detonated in their house, everything changed. Three of her friends were killed. Boudin was taking a shower when it went off and fled the scene. Photographs of a naked woman in the rubble circulated first in the media and then in flyers by the FBI, which attempted to locate her. Boudin would disappear underground for twelve years. She used hundreds of aliases. She cleaned houses. She gave up personal belongings. She lived a life of “politicized ascetism,” as Kolbert puts it (p. 3). In a way, the menial, isolated, and passive life also assured her: she had not chosen a route proximate to privilege, and which she feared replicating.

Boudin had just begun to turn her life around when she got arrested. A year before, she’d reached out to her parents, started using her own name, and repaired the relationship with David Gilbert, with whom she had a child. But she didn’t forsake her friendships nor her belief in black liberation. Twenty four hours before she was arrested, she’d met a member of the Black Liberation Army. For the rest of her life she maintained that she didn’t who was involved or how the robbery would ensue. Her aim was to “put myself at the service of a Third World group” (p. 24). She continued:

My way of supporting the struggle is to say that I don’t have the right to know anything, that I don’t have the right to engage in political discussion, because it is not my struggle. I certainly don’t have a right to criticize anything. The less I would know and the more I would give up total self, the better—the more committed and the more moral I was. (p. 24)

Boudin’s story in part inspired Philip Roth’s Pulitzer Prize winning novel in 1997, American Pastoral, which was adapted into a movie directed by and starring Ewan McGregor. Sixteen-year-old Merry Levov joins a group like Weather Underground, blows up a post office, and kills a person. Like Boudin, she disappears underground. Like Boudin, she comes from a Jewish family that has assimilated and achieved economic security. And like Boudin, she adopts a philosophy in which personal self-renunciation mingles with a belief in political violence. As the literary critic Ross Posnock explains, “Bringing Merry Levov and Kathy Boudin together makes clear that Roth grasps the specific psychic dilemma of the female terrorist, as Merry rehearses what Kathy Boudin will experience: the regression to extreme female passivity after violent assertion of will” (Posnock, 2018, p. 5). Merry is the twisted mirror image of her father, Posnock observes. Just as Merry’s father accepts the American idea of happiness—assimilation, comfort, deracination—she bows to the radical expectations of her organization. As Posnock observes, both “fail[] to articulate anything but submissiveness to unquestioned ideals” (Posnock, 2018, p. 5).

(Source: Wikipedia)

Creating Change in the Penal 1990s

But Roth, ever the misanthrope, never asks one question: Is Merry—is Boudin?—redeemable? What would a meaningful life have looked like for Merry following her violent act? What does a worthy aftermath look like? Is there a path for living in a way that is active, decisive, alive, ethical?

The story of how Boudin lived after her arrest provides an answer. In prison, she built a life of meaning and action. She insisted upon the interdependence of people, the dignity and generosity of incarcerated women. In her own activism she was ahead of her time or deeply in touch with it. “Women in prison are not just victims and they are not just problems. Understanding this is critical to a discussion about what is possible for women in prison” (Boudin, 2007a, p. 20). She insisted that they be recognized for what they are: women who have solutions, who can drive the process, who can create change.

To be sure, one might reply that imagining such an aftermath for Boudin is too sentimental for Roth. In American Pastoral he does not even bother devising an ending for Merry: she simply drops out. The last we see her, she’s malnourished, self-destructive, withering away in a filthy room, still living underground. For Roth, the “American berserk,” as he calls it, is an inescapable cycle of violence and punishment. Reconciliation is impossible. We cannot save ourselves: we are trapped in the interplay of generational pathologies.

But I suspect there’s another reason for Roth’s disinterest in the possibility of redemption: it merely reflects the extraordinarily penal, revenge-centered philosophy of punishment that began under Nixon and climaxed in the 1990s. During this time, there was simply no major public conversation about alternatives to prison, the possibility of restoration, and the humanity of people inside of it. Democrats had moved to the center, co-opting the Republican agenda on crime. Scarred and haunted by Michael Dukakis’s loss in his presidential run in 1988—a loss attributed to the notorious Willie Horton ads that preyed on fear of crime and the racism of American voters—they competed with Republicans to look tough on crime. In 1994, President Clinton signed a disastrous bill that eliminated Pell grants for prisoners, which essentially shut down college programs for prisoners across the country. Of the 350 college programs in prison across the country, only eight remained (Boudin, 2007, p. 19). In 1996, a year before Roth’s novel was published, the Oklahoma city bombing re-energized pro-death penalty factions and consolidated the power of the victim’s rights movement. That year, Congress passed the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act, probably the single greatest barrier for state prisoners to get their habeas petitions reviewed by appeals courts. It also passed an immigration bill that made it easier for courts to deport people convicted of petty crimes.

Meanwhile, the decade saw the birth of Three Strike statutes across America. These draconian laws mandated a 25-year to life sentence for people with two previous offenses. Two cases would make it to the Supreme Court. Leandro Andrade, a veteran, stole nine children’s videotapes from Kmart and received two consecutive 25-year terms—he stole from two different Kmarts—yielding a sentence of fifty years. Gary Ewing stole three golf clubs and received a 25-year to life sentence. In 2003, the Supreme Court declared the sentences of Andrade and Ewing constitutional, reasoning that Three Strikes statutes reflected the will of the people.

Women’s rights provided, in part, the moral rhetoric and legitimizing force for penal policies. In the two decades following the mid-1970s, a coalition of crime victims, feminists, and conservative “law-and-order” activists worked together to exert enormous influence on the criminal justice system (Barker, 2007). In the 1970s, the federal agency Law Enforcement Assistance Administration (LEAA) inundated all states with a total of approximately $1 billion a year in funding to counter domestic violence and rape. This funding had “significant strings attached” (Gottschalk, 2006, p. 145). Directed toward building victims’ services into law enforcement and prosecutors’ offices, the strategy ensured that victim’s rights were tied to one goal: increasing the number of criminal prosecutions. In some cases, domestic violence shelters and rape crisis centers that did not cooperate with law enforcement had their funding cut. Women’s rights groups replayed the “rape scare,” positing a white affluent female victim of a dangerous black rapist. A survey of victims’ rights organizations from the 1980s revealed that activists tended to be “overwhelmingly white, female, and middle-aged—a group demographic that is hardly representative of crime victims in general’” (Gottschalk, 2006, p. 90). The efforts of women’s rights victories arguably culminated in the passage of the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) in 1994, which poured funding into law enforcement agencies and mandated arrest of at least one person in a situation of domestic violence. Steeped in a language of retribution, and armed with the moral authority of having suffered harm, the “victims’ rights movement” unleashed a new emotional register in which to talk about crime. This movement was even cited by Justice Scalia when he found Three Strikes constitutional.

Meanwhile, groups with alternative visions of what “victims’ rights” might entail—especially African-American feminist groups—questioned how solutions that exclusively involve arrest and incarceration would affect Black and immigrant families. They demanded funding for mental health treatment, offender rehabilitation, and early models of restorative justice, including victim-offender mediation (Gottschalk, 2006). They charged the women’s rights movement for bolstering the legitimacy of a system that convicted primarily men of color. They noted the silence of mainstream feminists on issues that affected Black women. Black women were eight times as likely to go to prison as white women, mainly for drug-related offenses. (Guy-Sheftall, 2003, 178). Their criticism would prove to be true: since the passage of VAWA, police have arrested women as well in domestic abuse situations, sometimes in cases of self-defense. These policies today are more widely known as “carceral feminism.” Not all victims of domestic abuse want partners to be incarcerated; many want rehabilitated, employable partners who can provide economic and emotional support for their families.

In prison, Boudin bore witness to the punishing state and its often racist logic. An incarcerated middle-class white woman who had taken part in radical liberation movements, she was in a unique position to observe the near total absence of Black and immigrant women in public discourse. She was particularly struck by the invisibility of women who commit violent crime. She watched her friends return to the cell year after year after getting rejected by parole boards. This was especially demoralizing, Boudin wrote, to the younger women in prison, who looked up to the failed parole applicants. In some cases, the rejected applicants were completely rehabilitated: they facilitated programs, directed parenting groups, provided mentorship, and ran libraries. But for the parole boards, women were frozen in the crime they had committed years, sometimes decades, before.

It was during the HIV/AIDS crisis in the late 1980s that first galvanized Boudin. Nearly 20% of the women entering the correctional system tested positive for HIV in 1987. HIV/AIDS was the leading cause of death among black women between the ages of 25 and 44. One in 160 black women was infected, and they were ten times more likely than white women to die from it (Guy-Sheftall, 2003, p. 178). In prison, women died weekly, and, because it was heavily stigmatized, nobody spoke about it. Intense fear permeated the institution. Some were former or current drug users, terrified they were infected; others were family members of infected people. There were 800 women at the prison and no more than a handful of brief visits from professionals.

Boudin’s activism began with a seemingly simple project: quilt-making. She and other women stitched quilts to honor women who had died of AIDS. They displayed the quilts across the facility. Hundreds of women could see them. The simple acknowledgment of the dead was powerful. “AIDS was no longer hidden or whispered about,” she wrote. “It was suddenly something to talk about” (Boudin, 2007a, p.17) The quilt-making, in turn, led for people to be able to ask for more: education about how to avoid AIDS, how to educate their family members and loved ones about it.

In prison they had to tread lightly. Organizing is difficult anywhere, but in prison, there’s the added act that you can’t use the word “organize” (Kolbert, 2001, p. 6). You ask for permission; you create programs, or you ask to “facilitate.” These are the words acceptable to prison officials, who abhor the idea that their authority is being undermined or challenged. Becoming educated is always threatening to officials, Boudin explained, because an educated person knows to ask for more. AIDS education was particularly touchy, because it “requires talking about sex and drugs both of which are illegal in prison, and corrections personnel did not want to acknowledge they both happen in prison” (Boudin, 2007, p. 17). The prison eventually granted them permission to allow HIV/AIDS educators to enter the prison; this was a major victory. “We wanted to create a community within the prison; we wanted to take care of our sisters who were dying in front of our eyes, and prevent others from getting sick. We, women prisoners, drove this process” (Boudin, 2007a, p. 17).

“We Start from Our Own Loss”: Incarcerated Mothers and The Move to Repair

For incarcerated mothers, separation from children is the most excruciating part of being in prison. “I first faced the reality that I had left my fourteen-month-old child at the babysitter,” Boudin wrote. “I had ruptured a most basic human bond, violating a mother’s responsibility to protect and care for her baby … In our first visits after a two-month separation, he seemed not to recognize me—his mother, who had breastfed him for a year” (Boudin, 2003, p. 1).

But the existence of children also provides hope and impetus to change. This was so for Boudin. Not long after she was arrested, it was her mother told her that she had to go on, for the sake of her son. The words stayed with her. In her first months Boudin focused on how to help him: she chose the new adoptive parents, crocheted stuffed animals. Eventually, she said, after two months, he recognized her. “My awkward efforts to care for this one life, whose trust I had betrayed,” she wrote, “nourished my own humanity and was the first step toward repairing the human bonds that I had violated” (Boudin, 2003, p. 1).

Boudin sought to create spaces where mothers could talk about their efforts to repair. One major barrier was stigma, which left them feeling helpless and ashamed. They are the “bad mother who left her children,” “the crack or drug addicted mother.” As her co-author Roslyn Smith put it, “We always hear, as inmates, that we’re the scum of the earth. That’s what they think of me? Then that’s who I’ll be” (Boudin and Smith, 2003, p. 256). Violence, drugs, and abusive childhoods tend to be part of the story. “Where was I when my children needed me?” one woman in her group would say. “I was with a man, working, drugging. Drugging became my total existence. When the kids called, “Mommy,” I felt nothing” (Boudin and Smith, 2003, p. 256). Boudin quotes one woman, Tareema, who remembers

As a child I was beat for things I didn’t do. My mother broke my arm. I lived with violence between my parents. I was raped by my father from when I was age six to age thirteen and a half. (p. 248)

Another woman, Iris, who was shy and didn’t speak for weeks, shared:

During my pregnancy I got messed up—punches, black eyes, put in ice. I could see it coming in his face, so I’d put the kids in their room when I knew I’d get hit. My parents kept saying “Don’t leave your husband.” To outsiders, women are always the ones at fault. (p. 248)

Through these parenting groups, women develop a way to talk about their own loss and sources of shame. This loss, in turn, allows them to think about the victims of their crime. “We start from our own loss, and our arms reach out to embrace those we have harmed,” Boudin writes. “I learned that in holding on to our common humanity we can prevent ourselves from doing terrible things to one another” (Boudin, 2003, p. 2). Acknowledging the pain of one’s loss, in turn, creates empathy for people whom she has harmed:

In parenting classes, anguishing, we asked, “How could I have left my child? How can I answer her questions? How can I nourish him from here?” Sister Elaine, who created our Children’s Center, believes a person can do something terrible, learn from it, and then change and make a difference in our kids’ lives. A woman grieves for her children growing up without her. Then she watches a parenting video about teens’ lives destroyed by drugs and cries out, “Oh my God, the drugs I sold could have done that to other children.” (p. 2)

Acknowledging her own loss, in turn, helped Boudin make sense of the grief of the victims affected by the crime. The three men killed in the 1981 robbery left behind, in total, nine children. Before Boudin left prison, she published a short essay that sought in part to address the question of victims and their grief. “I want to know about [their] suffering, to face the anger, to say ‘I am sorry,’ because those words are the only ones we have to ask for forgiveness,” she wrote. She wished to tell them herself, but one primary rule is to never contact the victims. By some coincidence relating to the AIDS crisis, however, Boudin has met one person affected by the crime, a daughter of an eighty-year-old woman.

She told me her experience of that ghastly day: a gun stuck at her head, her eighty-year-old mother pushed out of her car, which had been commandeered. She testified against me and all who were arrested, a witness for the prosecution for three long years, and proud that she had helped to put everyone in prison. She asked me questions, and visited year after year. She allowed me to hear the consequences of my acts and to apologize. As I became a human being in her eyes, she forgave me. She helped me to experience my own humanity. There are many others whom I must face, others whose lives were devastated by irreparable loss and death. (p. 2)

Boudin’s emphasis on the connection between loss in one’s own life and empathy for those whom she has harmed echoes a philosophy of restorative justice. Such a concept was not yet in vogue during her time but the work of practitioners such as Danielle Sered, Sujatha Baliga, and Mariame Kaba have pushed it into the mainstream (Kuo, 2020). As Sered explains, restorative justice gives victims the chance to confront the people who hurt them, and to tell them how they were hurt. Offenders, in turn, have the chance to “face the people whose lives they’ve changed, as a full human being who is responsible for the pain of others” (Sered, 2019, p. 103). Sered emphasizes that restorative justice does not ask for the victim’s mercy, which “fails to … constitute justice on its own” (Sered, 2019, p. 95).[1] Philosophies that emphasize mercy not only minimize the pain of victim, but tend to fail to imagine the intensity of offenders’ own feeling and experiences: shame, hurt, indifference, denial, refusal to change, or, in some cases, desire to prove that they can change. As Sered explains, in traditional punishment a person is punished for something; restorative justice holds that a person “is not just accountable for something, but also to someone” (Sered, 2019, p. 114).

Still, there was no reconciliation in the case of the most direct victims of the 1981 killings. For years family members organized to oppose her application for parole. In 2001, the group was effective in its efforts; Boudin was denied parole. In 2003, she applied again. This time she was granted it. This decision caused public controversy, and two members of the parole board had to resign. Diane O’Grady, a widow of a slain officer, stated, “She raised her son while in prison. So this child was held and loved, and yet what about our kids? The only sentence that is justified to any of us is life” (Kolbert, 2001, p. 8). Meanwhile, Boudin advocated for restorative justice after she was released, facilitating programs that brought juvenile offenders and victims together in prison.

“Paradox of Intimacy”

For twenty two years Boudin thought and wrote about how to mother from prison. When she left, she turned her attention to their children who lived on the other side of the wall. She reunited with her own son Chesa and soon after enrolled in a Ph.D. program at Columbia. As part of Boudin’s dissertation research, she participated in Dynamic Teen, a peer group that brought together teenagers with incarcerated mothers, and interviewed eight youth who took part in it. The mothers helped in part to design this program, but it was the teenagers who worked to welcome new peers and to create support on the outside.

One of the poignant aspects of Boudin’s work is her insistence on the closeness of the relationship between incarcerated mothers and their teenage children. Mothers found ways to express love from a distance. Children learned to receive it and give it back. This is what Boudin terms a “paradox of intimacy” (Boudin, 2007, p. 142). Many might assume that prison prevents closeness between mother and child, she writes. But her research showed the opposite. Nearly all eight subjects were separated from their mothers for the entirety of their teenage lives; at least one knew his mother exclusively through the prison visits. Yet, she writes, all “had significant, complex and enduring relationships with their mothers, filled with knowledge of their mothers’ strengths and vulnerabilities…and with conflicted yearnings for closeness and distance” (Boudin, 2007, p. 183).

Separation intensifies the desire for connection, Boudin explained. Mothering across separation requires the child and parent to be “active and deliberate” (Boudin, 2007, p. 186). For reasons both practical and philosophical, mothers in prison are “more likely to listen and give quiet advice” (Boudin, 2007, p.272). The kids, in turn, appreciate the chance to see their mother. As one teenager said, “Every month, there was something new to tell, like you’re just saving up all month, then once you got there you just let it loose and she’d take it all in” (Boudin, 2007, p. 192). Or as another teenager put it, “I think it’s an even better relationship than most of my friends have with their parents. Because…you learn to appreciate them more, you know, not being able to see them … seeing them is like a privilege now” (Boudin, 2007, p. 192).

For teenagers, the peer group provided by Dynamic Teen was essential. Going to the prison with peers their age normalizes the incarceration of their mothers. As children, they might have felt glad to spend a Saturday visiting their mothers individually. But teenagers want to feel accepted by peers and don’t like to miss out on socializing opportunities. A one-on-one-meeting with their mother might be stifling or awkward. In a peer context, suddenly their mother “was able to be a normal mother, known by others as ‘your mom’” (Boudin, 2007, p. 244). The teens described this peer group as an extended family with which they could share their mothers. Their mothers also become aunties or mentors to their friends, becoming networks of care and support. Teenagers adopted their peers’ mother as an aunt, played games together, talked, ate together. They saw that their mothers had put in a lot of work to create a program for them. More, they saw their mothers “in roles other than mothers: as artists, coordinators, caregivers, peers of others” (Boudin, 2007, p. 244).

The programs that Boudin observed created rites of passage, from birthday celebrations and graduation ceremonies. Mothers expressed “avid interest in everything that their teenage children were doing.” More, “the physical contact of simply being together” could fill in silences. Mothers or daughters braided hair, or gave and received massages; these would “actualize the intimacy” (Boudin, 2007, p. 272). Mothers celebrated their children’s birthdays by getting cake with candles. As one teenager Sean said, “Some people don’t even get a happy birthday for their birthday, or nothing tangible. [T]hat your mom actually went out of her way to prepare something from her to you is something nice to think about…. she cares. She remembers” (Boudin, 2007, p. 255). Another tradition—the high point—was a graduation ritual created and put on by the mothers. They called it The Celebration of Achievement, and it marked their children’s graduation from their grade.

The teenagers also designed aspects of the program themselves. For instance, they wrote a questionnaire that formed the basis for conversations. Its style, personal and direct, offers a glimpse into the sorts of conversations teenagers had. Reagan, fourteen, responded to the questions this way:

What is it like coming up here to Northrup CF?

It’s like coming to a hangout spot where mothers are allowed.

What do you expect when you come here?

Time to spend with my mother I can’t at home.

How would you feel about kids coming up to your face and asking you a whole bunch of questions about your mother? How do you handle it and what kind of advice would you give other kids about how to handle it?

Well, I see it this way: it’s none of their business.

How do you handle pressure from friends about where your mother is?

I don’t, because I don’t talk about my mother to my friends.

What is it like being a young person and knowing that your mom is in jail?

It’s hard to focus on a lot of mother and daughter activities that go on when I can’t attend.

Hector, who is fourteen, responds in this way:

What do you like best about coming up here?

Seeing my mom.

….

What helps you deal with the fact that your mother isn’t home? What advice would you give to other kids who face your situation?

Don’t do what I do. Talk about how you feel.

What is it like being a young person and knowing that your mom is in jail?

It hurts because you know that your mother isn’t home and all they ever do is talk about their mom. I get jealous. (p. 320)”

Thus in the years after prison, Boudin transformed herself again, to that of a researcher connected to the project of social justice and the children of incarcerated people. “I am involved in research to learn, to investigate; I see myself in the tradition of researchers who want their research to contribute to a better world, who interrogate both oppression and possibility, and who work from a position of social responsibility,” she writes. She hoped that writing narratives of young people and their work to create change in their lives would shed light on the impact of the social policy of incarceration.

The New Era

I was born the year Boudin was arrested. I read American Pastoral when it came out in hardcover, on a couch in my parents’ home in western Michigan. The impression it left on me was that young Merry was troubled, spoilt, complicated, and self-destructive. Some six years later, in 2003, I met Boudin’s son Chesa at, of all places, a Rhodes Scholarship finalist interview. He won (I did not), and I would learn the Boudin family story through a New York Times piece describing his victory of the most prestigious scholarship in the world in semi-provocative terms.

Chesa would continue his mother’s work. He advocated for children of incarcerated parents, became a public defender in San Francisco, and was elected as part of a “progressive prosecutor” movement in the United States. Among the core tenets of this movement is that prison should not be regarded as a solution to social problems such as poverty and mental illness. His office created a wrongful conviction unit that led to the exoneration of a man who had been imprisoned for 32 years for a murder he did not commit. He banned the use of crime victims’ DNA in criminal investigations.

(Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Reading his mother’s work from the 2000s, I’m startled to see how cutting-edge it was. She was writing perceptively about issues that only recently, in the past five years, have reached the mainstream: restorative justice, with its beliefs in repair and accountability; Black Lives Matter; the need to humanize those who commit violent crime; the impact of children separated from their incarcerated mothers. It was her proximity to the expansion of American penality that allowed her to be prescient and clear-eyed. This isn’t to say that crime is not fraught, controversial, and divisive. Chesa was recalled in a deeply divisive campaign that portrayed him as soft on those who have committed property crimes. Still, the fact that he was elected on principles that were previously considered fringe should be reason for hope.

And what of Taiwan? Our history is also a revolutionary one. It’s a mark of Taiwan’s remarkable democratization that incarcerated political dissidents from the 1960s to the 1980s became respected and beloved leaders upon release. In prison they discovered what Boudin did: it is a place where, against all odds, people find and create solidarity. Among these incarcerated revolutionaries were women freedom fighters who nursed their children in prison. Still, Taiwan has a long road to travel when it comes to public attitudes towards incarceration, which remains heavily stigmatized. Boudin’s writing and life shows us a way forward. We need public dialogues about the origins of crime, the humanity of people in prison, the possibility of restoration and change, and the effect of incarceration on people’s families. We need social action centered around the principle that Boudin passionately believed: people with problems are people with solutions.

No matter the country, questions about incarcerated people always end up circling back to the crime. What of hers? How do we think about it four decades later? In the past five years California voters have rejected the harsh penalties for “felony murder,” a common law concept inherited from the United Kingdom. That’s the category that charges getaway drivers for murder. Then there’s the broader question of political violence. Rereading Roth, whose writing I admire, I am nonetheless struck by the contempt he had for the radical youth of the 1960s. The desire of those such as Boudin to “bring the war home” took seriously that notion that a Laotian life was equal to an American one; that taxpayer money was paying for chemical weapons that killed and deformed Vietnamese people; that Black people in America could be killed and arrested indiscriminately by police. More, the example of Algeria was still fresh on everyone’s minds; theirs appeared to be a lesson about violent resistance as having ousted colonial occupiers. I do not endorse bombing or taking a life. But I do think that the world the young inherited was burning, violent, and off the rails.

Nonetheless, while incarcerated, Boudin never tried to defend her past. This acceptance of responsibility forms a core part of her own dignity. “I look back on my crime and know that I would never again be involved in anything that risked human life in the name of social change,” she writes. “I am not the woman who was arrested twenty-two years ago. I am a mother deeply connected to the world, whose child, now a young man, has led me over and over to understand the nature of loss and love. Remorse will always guide me. It is a very personal journey with stops along the way. It is a road with no end” (Boudin, 2003, p. 2).

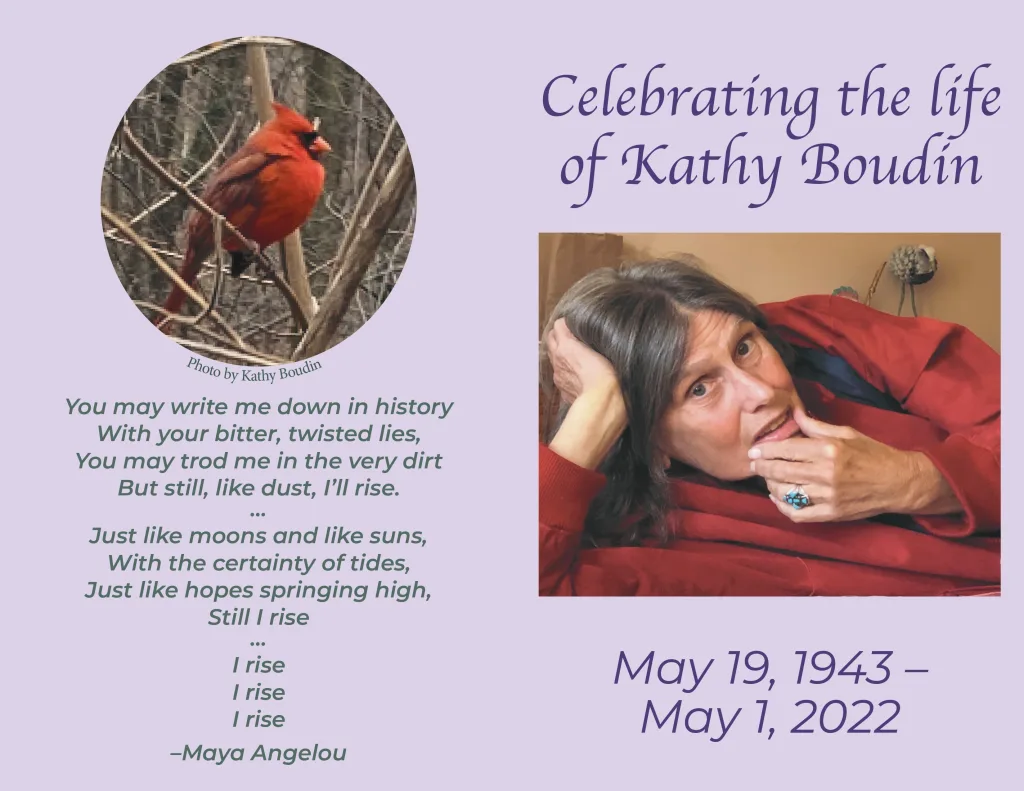

Last fall, Boudin died at the age of seventy eight. Her service drew hundreds of people who remembered her generosity, vision, optimism, and desire to help others in need. Bernadine Dohrn, Chesa’s adoptive mother, spoke of the unique co-parenting strategy that she and Boudin had created. Angela Davis, a high school classmate of Boudin’s, spoke of her extraordinary capacity to be present with every person she met. That quality was remarked upon repeatedly. “Hundreds of people have told me they never met anyone who listened so much, cared as much,” said Chesa, whose eulogy closed the service. He hoped to carry that spirit “into every human interaction.”

Chesa spoke of the adventures they had taken upon release—canoeing in the Amazon, planting gardens in Northern California. But he also returned to his memories from youth. When his mother was in prison, she would send him audio cassette tapes of her reading stories or singing songs. Growing up, he would listen to those cassette tapes over and over again:

I love you, rewind. I love you, rewind. I love you. Rewind.

(Source: Center for Justice at Columbia University)

(Source: Center for Justice at Columbia University)

[1] Sered runs a nonprofit called Common Justice, the first program in the United States to offer restorative justice as an alternative to prison for people who have violent crimes. “I had to go through my own hurt too,” says Donnell, who was charged with a violent felony and participated in Common Justice. “I had to deal with that part of myself” (Sered, 2019, p. 146). Through facing the people he harmed, he says, he started to “feel a connection” to those who have been hurt (Sered, 2019, p. 146).

References

Barker, Vanessa (2007). The Politics of Pain: A Political Institutionalist Analysis of Crime Victims’ Moral Protests. Law & Society Review, 41(3), 619-664. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5893.2007.00316.x

Boudin, Kathy (2007a). The resilience of the written off: Women in prison as women of change. Women’s Rights Law Reporter, 29(15), 15-22.

Boudin, Kathy (2007b). “Children of Promise”: Being a teen with a mother in prison and sharing the experience with peers [Doctoral dissertation, Teachers College, Columbia University]. Proquest Dissertations Publishing. https://www.proquest.com/pqdt/docview/304859688/403A3351121F4EEEPQ/1?accountid=14229

Boudin, Kathy (2013, April 10). Kathy Boudin on Making a different way of life. Patheos. https://www.patheos.com/articles/making-different-kathy-boudin-04-11-2013

Boudin, Kathy, & Smith, Roslyn D. (2003). Alive behind the labels: Women in prison. In Robin Morgan (Ed.) Sisterhood is forever: The women’s anthology for a new millennium (pp. 244-268). Washington Square Press.

Center for Justice at Columbia University. (2022, September 11). Kathy Boudin Memorial [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PnZfTNq70aI

Gottschalk, Marie (2006). The prison and the gallows: The politics of mass incarceration in America. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511791093

Guy-Sheftall, Beverly (2003). African-American women: The legacy of black feminism. In Robin Morgan (Ed.) Sisterhood is forever: The women’s anthology for a new millennium (pp. 176-187). Washington Square Press.

Kaba, Mariame (2021). We do this ’til we free us: Abolitionist organizing and transforming justice. Haymarket Books.

Kolbert, Elizabeth (2001, July 8). Kathy Boudin’s dreams of revolution got her twenty years behind bars. Should she now go free? The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2001/07/16/kathy-boudin-profile-the-prisoner

Kuo, Michelle (2020, August 20). What replaces prisons? The New York Review of Books. https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2020/08/20/what-replaces-prisons/

Posnock, Ross (2018). Homegrown American terrorists: Merry Levov (of Roth’s American Pastoral) & Kathy Boudin. In Ettore Finazzi-Agrò (Ed.) Toward a linguistic and literary revision of cultural paradigms: Common and/or alien (pp. 3-8). Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Sered, Danielle (2019). Until we reckon: Violence, mass incarceration, and a road to repair. The New Press.